SPAKE2 Interoperability

I've been working on a Rust implementation of SPAKE2. I want it to be compatible with my Python version. What do I need to change? Where have I accidentally indulged in protocol design, so a choice I make in this library might cause it to behave differently than somebody else's library? How can I write unit tests for interoperability?

This post walks through the parts of the SPAKE2 protocol that a library author must decide for themselves how to implement, most of which have a direct bearing on potential compatibility with other libraries. It describes the choices I happened to make while writing python-spake2, none of which are necessarily the best, effectively (but accidentally) defining a specification of sorts.

Left As An Exercise For The Programmer

The SPAKE2 paper, like most self-respecting academic publications, leaves out a lot of details that would be necessary to build a specific implementation. Authors get tenure points for inventing new protocols and breaking existing ones, but unfortunately not for the necessary engineering work of defining test vectors and data-serialization formats.

If you want to actually implement the protocol, you must answer a number of extra questions (listed below). For your program to interoperate with someone else's, you must both use the same answers. For protocols that are "grown up" enough, folks like the IETF will publish RFCs with those details. SPAKE2 is not there yet (RFC8125 defines some considerations, and the CFRG has an expired draft), so lucky us, we're on the cutting edge! The first few implementations might choose mutually-incompatible approaches, but eventually we can learn from each other and agree upon something interoperable.

The 0.7 release of my python-spake2 library incorporates some decisions we made on pull request #273 of the SJCL Project (a pure-javascript crypto library), where we were able to hash out a mostly-interoperable pair of libraries (python and JS). Some of the discussions there may be useful. Jonathan Lange and JP Calderone are working on haskell-spake2, and I'm working on a Rust library, and we're all aiming for compatibility with python-spake2.

I'm going to call this set of decisions the "0.7 protocol", to emphasize my hope that some day we'll get a fully RFC-blessed specification (deserving of the name "1.0"). When that happens, I'll update python-spake2 to implement 1.0, and provide an "0.7 mode" for backwards compatibility with older clients.

SPAKE2 Overview

SPAKE2 belongs to a family of protocols named PAKE, which stands for Password-Authenticated Key Exchange.

The SPAKE2 protocol helps two people who start out knowing some shared secret code or password. It lets our Alice and Bob exchange messages (one each), and then both sides calculate a secret key. If Alice and Bob used the same code, their keys will be the same, and nobody else will know what that key is.

You can imagine that Alice gives the code (and some other identifying data) to her friendly local SPAKE2 Robot, which she bought off the shelf at SPAKE2 Robots R' Us. The robot gives her a message to deliver to Bob's robot. Meanwhile Bob is doing almost exactly the same thing. When Alice gives Bob's message to her local robot, her robot prints out a random-looking key. At the same time, Bob gives Alice's message to his robot, and his robot prints out (hopefully) the same key.

Both Alice and Bob have to tell their robots that the first person playing this game is named "Alice", and the second person is named "Bob". They must also tell their robots who is who: Alice must say "Robot, I'm the first person, not the second", and Bob must say "I'm the second person, not the first". That last item, the "side", is the only thing which they do differently.

Internally, these robots are going to generate some random numbers, do some math, generate a message, accept a message, do some more math, assemble a record of everything they've done and seen and thought into a transcript, and then turn the transcript into a key. Part of the transcript will be secret, which is what makes the key secret too.

Your SPAKE2 Library API

The first thing to define is your local library API (the "SPAKE2 Robot"). This isn't completely exposed externally, of course: different libraries with different APIs (in different languages) should be able to interoperate if they can agree on all the other decisions we'll explore below. But you don't have complete freedom either: some constraints bleed through. We must glue together local API requirements, the wire format, and the SPAKE2 math itself.

We'll consider some application that sits above the library. You, as the library author, are providing an API to those applications. You don't know what they need SPAKE2 for, or how they're going to use it, but your job is to enable:

- safety: give the application author a decent chance of getting things right

- interoperability: enable compatibly-written applications (perhaps using different libraries, in other langauges) get the right results when run against an application using your library

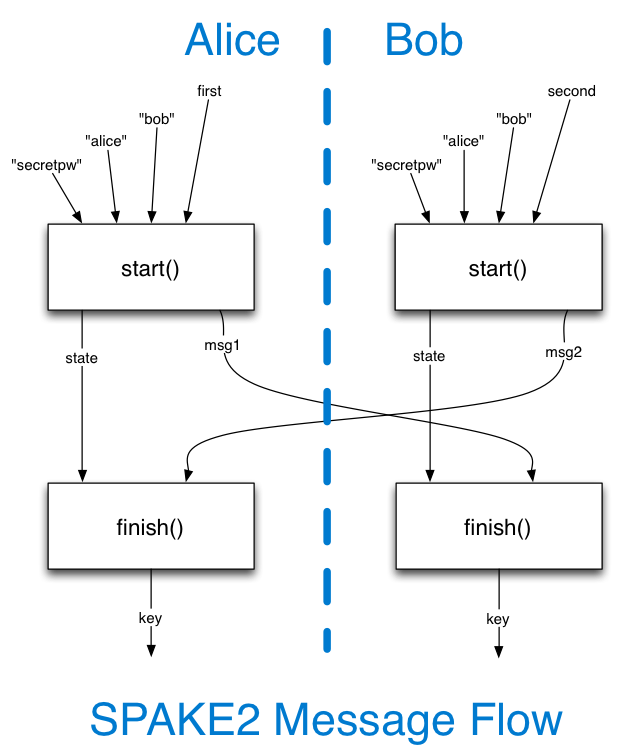

The library API we need to provide is pretty simple, and basically consists of two functions (but which could be expressed in different ways):

(msg1, state) = start(password, idA, idB, side)

# somehow send msg1 to the other party

# somehow receive msg2 from the other party

key = finish(msg2, state)

# do something with the shared key

start() will accept the password (probably as a bytestring, but

maybe as unicode), the identities of the two sides, and some way to

indicate which side this instance is playing. It's a nondeterministic

function (since it must pick a random scalar), so some languages will

require passing in a source of randomness, but to be safe, application

code should not be required to deal with this. The first function

returns two things: an outbound message to be sent to the peer, and a

state object to be used later.

finish() is deterministic. It accepts both the state object and a

message received by the peer, and emits the shared key (as a

fixed-length bytestring). The length of the shared key is up to the

library author, but it's typically 256 or 512 bits (since it's the

output of the transcript hash). Applications that need more key material

should derive it from the shared key with

HKDF, outside the scope of the

SPAKE2 library.

You run both halves of the API on both sides. Each side will generate one message and accept one message. Two messages are generated in all.

The outbound message will be a bytestring, and the application will be responsible for encoding it in whatever way is needed for the channel (e.g. the app might need to base64-encode it to put into an HTTP header, but that's outside the scope of the SPAKE2 library). It will generally be of a fixed length for any given group (see below), but it may be easier to tell application authors to expect a variable-length byte vector.

The state object could be an opaque in-memory struct. For example, in object-oriented languages, the first function may be an object constructor, and the second is just a method call on that same object. If the object can be serialized, or if the first function returns a serializeable state object, then the application may be able to shut down and be resumed in between the generation of the first message and the receipt of the second (so the two users don't have to be online at the same time). If you offer serialization, make sure to warn authors against using the same state object twice, since this will hurt security.

For two different libraries to interoperate, they must use the same key length. They must also encode the same password in the same way, as well as the identities of the two sides.

The application author's responsibilities are:

- give their user a way to enter a code or password

- deliver that password to your library (the first function)

- take the message your library returns and deliver it correctly to some remote application

- take the matching inbound message from the remote application and deliver it correctly to your library's second function

- do something useful with the shared key

Symmetric Mode

My python-spake2 library also offers a "Symmetric Mode" which isn't defined by the Abdalla/Pointcheval paper. This is a variant that I developed, with help from Mike Hamburg and other crypto folks. It removes the "side" parameter from the API, so two identical clients can establish a key without pre-arranged knowledge of which one is which.

Protocol Definitions

The details that any given SPAKE2 implementation must define are:

- how to represent/encode the "identities" of each side

- what group to use

- what generator element to use

- how to represent/encode the code/password, both as a scalar and in the transcript

- what "arbitrary group elements" to use for M and N (and S)

- how to encode the group element that is sent to the other party

- how to decode+validate the group element received from the other party

- how to assemble the transcript

- how to hash the transcript into a key

If the library offers serialization of the state object, then it must also define a way to serialize and parse scalars, but this is private to the library, so it doesn't need to be part of the interoperability specification. Scalar parsing would also be needed by any private deterministic testing interface, described below.

Identities

The paper describes each side as having an "identity", such as a username or server name. The idea here is to prevent an attacker from re-using messages of one protocol execution in some other context. If Alice is intending to establish a session key with Server1, then her message should not be suitable for a similar process with Server2.

The protocol needs bytestrings (to put into the hashed transcript, since hashes need bytes), so the library API should require bytestrings.

The canonical example of an identity is a username, and of course usernames can include all sorts of interesting human-language characters, so the application may want to accept unicode strings, and convert them (deterministically) into bytestrings before passing them to the library. There are, unfortunately, multiple ways to convert weird unicode strings into UTF-8 (look up "surrogate pairs" sometime), but there's one recommended canonical encoding ("NFC") that should work for all but the strangest of inputs.

It's not entirely clear whether this conversion should be performed by the application or the library. The problem with doing it in the application is that using compatible SPAKE2 libraries may not be enough to achieve interoperability (if the applications encode differently), and everything will seem to work fine until a sufficiently novel username is encountered. The problem with doing it in the library is that it drags unicode into an otherwise somewhat clear-cut API, and hampers the application from using full 8-bit bytestrings if it should choose (perhaps the identities are public keys from some other system: they'd have to be encoded as unicode before passing into such an API).

My recommendation is to have the library accept a bytestring, but provide guidance on what the application should do with unicode identities (which should be "encode with UTF-8 and NFC").

The two identities must be given to start(), and must be included in

the state object so they can also be used inside finish(). They

should be passed as arguments with "A" and "B" in the names, so that the

other library gets them the same way around, even if the actual argument

names are different (e.g. idA vs identity_A).

If Carol and Dave are using this protocol, and Carol passes

idA="Carol" and idB="Dave", then Dave must also pass

identity_A="Carol" and identity_B="Dave". If Carol says

side=A, then Dave must say side=B.

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: bytestrings

- What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 does: bytestrings

- Symmetric mode: there is only one identity, named "idS", but it can still be set to an arbitrary string to distinguish between different applications

The Group and Generator

The details are beyond the scope of this post, but SPAKE2 uses "Abelian Groups", which contain a (huge) number of "elements". When our group is an "elliptic curve" group, each element is also known as a "point" (the elements of integer groups are integers, and other groups use other kinds of elements). So you'll see references to "point encoding" and "point validation". The other thing to know about groups is that there's a second thing called a "Scalar", which is basically just an integer, limited by a big prime number (which depends on the group). Sometimes you'll need to deal with group elements, sometimes you'll need to work with scalars.

Some groups are faster than others, or have smaller elements and scalars, or are more or less secure.

The Ed25519 signature protocol defines a group (sometimes named "X25519") with nice properties, but you could use others. My python library defaults to Ed25519 but also implements a couple of integer groups.

Both sides must use the same group, of course. Every group comes with a standard generator to use for the base-point "scalarmult" operation, and the group's order will constrain many other choices.

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: defaults to Ed25519, but offers 1024/2048/3072-bit integer groups too.

- What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 does: left as an exercise for the reader, but sample M/N values are generated for SEC1 P256/P384/P521, and Ed25519 gets a passing mention

Code/Password

The input password should be a bytestring, of any length (your library shouldn't impose arbitrary length limits). Any necessary encoding should be done by the application before submitting a bytestring to the SPAKE2 library (if the application needs to allow humans to choose the password, then it may want to accept unicode and perform UTF-8 encoding itself).

The same arguments for identities apply here, but I'm even more in favor of a bytestring API (rather than unicode), because it's entirely valid to have the password be the output of some other hash function (maybe you stretch it with bcrypt, scrypt, or Argon2 first), in which case requiring a unicode string would be messy.

The password is needed in two places. The first (and most complicated) is as a scalar, where it is used to blind the public Diffie-Hellman parameters. The second is when it gets copied into the transcript (see below).

For the first case, the password must be converted into a scalar of the chosen group. This is enough of a nuisance that PAKE papers like to pretend that users have hundred-digit integers as passwords rather than strings, so they can avoid discussing how to get from one to the other. We can't dodge this task: our SPAKE2 library will be responsible for this conversion.

Turning a password into a scalar is closely related to generating a uniformly random scalar, so see my previous blog post for some discussion about the process. To summarize, we don't need uniformity for SPAKE2, we just need to emit a non-negative integer less than some large prime number P (equal to the order of the group we're using), and preserve all the entropy of the original password distribution.

In practice, this means something like:

def convert_password_to_scalar(password_bytes, P):

pw_hash_bytes = sha256(password_bytes).digest()

pw_hash_int = int(binascii.hexlify(pw_hash_bytes), 16)

pw_scalar = pw_hash_int % P

return pw_scalar

We start with SHA256 to convert the arbitrarily-sized password into a fixed-size bytestring, and also reduce the chance that distinct pathological inputs (empty string, all-NUL) will give us distinct pathological scalars (like 0, which might not be good). Then we treat those 32 random-ish bytes as an integer, then take the result modulo P to make sure it's in the right range (no matter what P actually is).

In large groups (P > 2**256), this won't fill the whole range, but

that's ok. In any group, this will have a bias (smaller scalars will

occur more frequently than large ones), but that's also ok for SPAKE2

(the password isn't uniformly distributed in the first place). It's

definitely not ok for Diffie-Hellman: see

the blog post

for details. SHA256 is wide enough to preserve more entropy than any

conceivable password. A wider hash (SHA512, Blake2) would be fine too,

but e.g. a 16-bit hash would waste a lot of password entropy.

You might already have a function lying around which turns uniformly-random seeds into uniformly-random scalars: this is safe to use for the SPAKE2 password, but it's overkill, and you might get some funny looks from the standards committee.

Note that some crypto libraries store scalars as opaque binary structures (e.g. arrays of 51 bit integers, to speed up the math), even when the language has built-in "bigint" support. So your password-to-scalar function may need to use a library-specific large-integer-to-scalar-object function.

Both sides must perform this conversion in exactly the same way, otherwise they'll get mismatched keys. All aspects must be the same: the overall algorithm, the hash function you use, the way the hash output is turned into an integer (big-endian vs little-endian will trip you up), and the final modulo operation.

When I wrote python-spake2, I was (incorrectly) worried about uniformity, so I used an overly complicated approach (which mimics the Ed25519 random-scalar-generation code: hash the seed to a much larger range than is really necessary before moduloing down to P; this reduces the bias to a tiny fraction of a bit). If I were to start again, I'd use something simpler.

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: HKDF(password, info="SPAKE2 pw", salt="", hash=SHA256), expand to 32+16 bytes, treat as big-endian integer, modulo down to the Ed25519 group order (2^252+stuff)

- What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 does: left as an exercise, although key-stretching is recommended

Note that key-stretching only matters if the same password is used for multiple executions of the protocol. Stretching would be most useful on a login system using the SPAKE2+ variant. In SPAKE2+, the "server" side stores a derivative of the password, so a server compromise does not immediately allow client impersonation: this password derivative must first be brute-forced to reveal the original password, and each loop of this process will be lengthened by the stretch. In magic-wormhole, a new wormhole code is generated each time, and nothing is stored anywhere, so stretching is not necessary. I think key-stretching should be done outside the SPAKE2 library.

Arbitrary Group Elements: M and N

The M and N elements must be constructed in a way that prevents anyone from knowing their discrete log. This generally means hashing some seed and then converting the hash output into an element. For integer groups this is pretty easy: just treat the bits as an integer, and then clamp to the right range. For elliptic-curve groups, you treat the bits as a compressed representation of a point (i.e. pretend the bits are the Y coordinate, then recover the X coordinate), but you must make sure that the point is correct too: it must be on the correct curve (not the twist), and it must be in the correct subgroup.

Why hash a seed? We definitely want different values for M and N, we kind of want different values for different curves, and it would be cool to reduce our ability to fiddle with the results too much: the elements we pick should somehow be the most "obvious" choice. Another name for this property is the "nothing up my sleeve" number. djb's bada55 site (and the delightfully amusing paper) touch on this. Pretend that we're trying to build a sabotaged standard, defined to use an element for which we (and we alone) know a discrete log. Maybe we have some magic way to learn the discrete log of, say, one in every million elements. And say that instead of a seed, we're just using an integer. Now we could just keep trying sequential integers until we get an element that we can DLOG, and then we write this not-huge integer into our standard, and tell folks something like "oh, 31337 was my first phone number, so that was the most obvious choice", muahaha.

Using a short seed, named something obvious like "M", gives us a warm fuzzy feeling that there's not much wiggle room to perform this hypothetical search for a bad element. It's not perfect, though, since we can probably just wiggle the other aspects (which hash to use, which other fields to include in the hash, the order to arrange them, etc). So hash-small-seed is nominally a good idea, but the real safety comes from the choice of group and the hardness of the DLOG assumption.

Using a string seed that includes the curve name means we'll definitely get different (and quite unrelated) values for different curves, but to be honest using different curves pretty much gives you that anyways, and it's not clear how similar-looking elements in unrelated curves could be used as an attack anyways. The general concern is that you might use the same password on two different instances of the protocol (one with each curve), and then an attacker can somehow exploit confusion about which messages go with which curve.

So that's how get a "safe" element. Nominally, this only ever needs to be done once: in theory, I could publish the program that turns a seed of "M" into 0x19581b8f3.. in a blog post, and then just copy the big hex values into python-spake2, and include a note that says "if you want proof that these were generated safely, go run the program from my blog". And if you actually went and downloaded that code and ran it and compared the strings, then you'd get the same level of safety. But nobody will actually do that, so we can inspire more confidence by adding the seed-to-element code into the library itself, and starting from a seed instead of a big hex string.

(note that doing this at each startup may add a non-trivial slowdown to applications: a suitable compromise might be to hard-code the elements for the regular code path, but compare them against recomputed values in the library's unit tests)

Since we need all implementations to use the same M/N elements, this means we may need to port the specific seed-to-arbitrary-element routine from the original language (where maybe it was a pretty natural algorithm) into each target language (where it may seem overcomplicated).

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: HKDF(seed, info="SPAKE2 arbitrary element", salt=""), with seed equal to "M" or "N", expand to 32+16 bytes, treat as big-endian integer, modulo down to field order (2^255-19), treat as a Y coordinate, recover X coordinate, always use the "positive" X value, reject if (X,Y) is not on curve, multiply by cofactor to get candidate point, reject candidate is zero (i.e. we started with one of the 8 low-order points), reject if candidate times cofactor is zero (i.e. candidate was not in the right subgroup), return candidate. If the candidate is rejected, increment the Y coordinate by 1, wrap to field order, try again. Repeat until success. We expect this to loop 2*8=16 times on average before yielding a valid point. This happens at module import time.

- Symmetric Mode: a group element named S is constructed in the same

way, with a seed of

S, and is used for blinding/unblinding in both directions (where SPAKE2 says "N", replace it with S, and where SPAKE2 says "M", also replace it with S). - What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 does: find the OID for the curve, generate an infinite series of bytes (start with SHA256("$OID point generation seed (M)") for that OID to get the first 32 bytes, then SHA256(first 32 bytes) to get the second 32 bytes, repeat), slice into encoded-element lengths, clamp bits as necessary, interpret as point, if that fails repeat with the next slice. Do the same with "(N)".

Element Representation and Parsing (Encode/Decode)

Element representation is the most obvious compatibility-impacting decision to make, as the algorithm provides a group element (e.g. a point) for the first message, but our library API returns a bytestring (since we need to send bytes over the wire). So clearly we need to define how we turn group elements into bytes, and back again.

(while you could define the API to return an abstract element, and push the serialization job onto the application, that sounds unlikely to ever interoperate with other libraries)

The X.509 certificate world has a fairly well-established process for doing this, called BER or DER, and it includes things like multiple compression mechanisms and built-in curve identifiers. The security community has an equally well-established distaste for BER/DER, because the parsers are hard to implement correctly (and without buffer overflows), and these days flexibility is considered a misfeature.

For the Ed25519 group, points are represented as they are in the Ed25519 signature protocol: a 32-byte string, containing the Y coordinate as a 255-bit little-endian number, with the sign of the X coordinate appended as the last bit.

On the receiving side, the library must parse the incoming bytes into a group element. Obviously the encoder/parser pair must round-trip correctly for anything generated by our library, but it must also work safely for other random strings, including deliberate modifications of otherwise-valid values by an attacker (intended to force the key to some known value that's independent of the password). There is some debate about the issue, but for safety, the receiving side should reject any message which turns into:

- a point that's not actually on the right curve

- a point that's not actually a member of the expected subgroup

The former is accomplished by testing the recovered X and Y coordinates against the curve equation, which takes time. The latter is done by multiplying by the order of the group (the details of which depend upon the "cofactor"), and can take as much time as the main SPAKE2 math itself (so potentially doubling the total CPU cost). However both are important to do, and worth the slowdown: it will be trivial compared to the network delay.

Note that whatever crypto library you use will probably implement point-encoding and decoding for you. In general, this is great, because they probably did a much better job of it than anything we could do. But this also limits your ability to interoperate with a SPAKE2 function that uses a different crypto library. And check the docs carefully to make sure it's doing enough validation: you might be using a function that assumes the encoded values come from a trusted source (e.g. saved to disk), and that's not the case for us.

Finally, SPAKE2 is (usually) "sided": there are two roles to play, and both participants must somehow choose (different) sides before they start. A really common application mistake is to use the same side on both ends: "Hello Alice? This is Alice.". When this happens, the keys won't match, and the result will be indistinguishable from a password mismatch, which will take forever to debug.

To help programmers discover this error earlier, the library might want to add a "side identifier" to the message. If the second API function is given a message from the same side as it was told to be in the first function, it can throw an exception which instructs the programmer to assign different sides.

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: encode points like Ed25519 does, reject not-on-curve and not-in-correct-subgroup points during parsing. A one-byte "side identifier" is prepended to the outgoing message, and this identifier is checked and stripped on the inbound function.

- What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 does: specified by the choice of group, suggests SEC1 uncompressed or big-endian integers

Transcript Generation

Now that each side has sent their element, and received the other side's element, the SPAKE2 math gets us a secret shared element. However this isn't a key yet. The remainder of the protocol is responsible for leveraging this secret element in the production of a proper shared key.

The secrecy of the shared key comes entirely from the secrecy of the shared element (the original password is also involved, to make the proof stronger, but doesn't add any meaningful security). However using it alone would open us up to several mix-and-match attacks, where the adversary redirects and reorders messages to confuse e.g. an Alice+Bob session with an Alice+Carol session. In addition, the shared element isn't a uniformly random key: for starters it isn't even a bytestring. And serializing a random element doesn't get you a random bytestring: there are usually distinctive patterns, like the high bit is always set, or the low bits are always clear, or its value as an integer is always smaller than the group order. Our goal is a fixed number of independently uniformly random bits, usually 256 of them.

Modern protocols handle both these problems by building a "conversation transcript", which contains every message that was exchanged (as well as the "inner voice" intentions and computed secrets), and finally hashing the whole thing. The hash function hides any structure from the secret element, and the inclusion of the other messages prevents the mix-and-match attacks.

It's as if Alice's SPAKE2 Robot keeps a journal as it works, with the following entries:

- This a journal about a SPAKE2 conversation.

- I'm using a password of:

password - The first side's identity is:

Alice - The second side's identity is:

Bob - The first side sent a message to the second side with:

MESSAGE1 - The second side sent a message to the first side with:

MESSAGE2 - I derived a shared group element of:

SECRET SHARED ELEMENT

Except that everything in the transcript needs to be a bytestring. Bob's robot will have an identical journal: note that every statement is true for both sides (assuming the shared element works out), and nothing is specific to a given side (e.g. the phrase "I am Alice" or "I am the first side" does not appear).

The password could be hashed in its original form (as a bytestring), or as a scalar (which must then be serialized into a bytestring). We need the scalar form in both the first and the second functions, so you have a couple of choices of CPU and space usage (noting that both are miniscule):

- store only the bytestring in the state vector, and re-convert to a scalar in the second function, then hash the bytestring

- store only the bytestring in the state vector, and re-convert to a scalar in the second function, then hash the serialized scalar

- store only the scalar in the state vector, and hash the serialized scalar

- store both in the state, and hash the bytestring (this is my preference)

- store both in the state, and hash the serialized scalar

The messages could include the "side" marker, or not. Since the messages need to be bytestrings for transmission anyways, it makes sense to use these same encoded forms for the transcript too. The final shared element should be encoded in the same way as the messages were, although of course this encoded secret element is never sent over a wire.

The concatenation scheme must resist "format confusion" attacks: where the combination of (A1, B1) results in the same bytes as a combination of some different (A2, B2). This only really happens when either value can be variable-length, and the length is not correctly included in the combined form. For example:

def unsafe_cat(a, b): return a+b

assert unsafe_cat("youlo", "se") != unsafe_cat("you", "lose")

Adding a fixed delimiter is unsafe if the strings could contain the delimiter:

def unsafe_cat2(a, b): return a+":"+b

assert unsafe_cat2("you:lo", "se") != unsafe_cat2("you", "lo:se")

Escaping the delimiter can work, but is touchy (you must escape the escape character too). The rule is that if you could reliably parse the concatenated string back into the original pieces, no matter how weird those pieces were, then you've got a secure concatenation function.

Two safe and easy ways to do this are:

- prefix all variable-length strings with a fixed-size length field

- hash each variable-length string first, and concatenate the fixed-length hashes

def safe_cat(a, b):

assert len(a) < 2**64 # length fits in 8 bytes

assert len(b) < 2**64

return "".join([(struct.pack(">Q", len(x)) + x) for x in [a,b]])

def safe_hashcat(a, b):

return sha256(a).digest() + sha256(b).digest()

Of course, both sides must use the same order of elements, the same encoding for each element, and the same final concatenation technique.

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: transcript = sha256(password)+sha256(idA)+sha256(idB)+msg_A+msg_B+shared_element.to_bytes()

- Symmetric Mode: sort the two messages lexicographically to get msg_first and msg_second, then transcript = sha256(password)+sha256(idS)+msg_first+msg_second+shared_element.to_bytes()

- What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 does: len(idA)+idA+ len(idB)+idB+ len(B_msg)+B_msg+ len(A_msg)+A_msg+ len(shared_element)+shared_element+ len(password_scalar)+password_scalar

In draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03, len(x) uses 8-byte little-endian

encoding. The shared element is encoded the same way as it would be on

the wire. The hash uses the password scalar, rather than the password

itself. All fields are length-prefixed even though most of them have

fixed lengths. And for some reason (maybe a typo) B_msg appears

before A_msg, even though idA appears before idB.

Also note the context of that draft's protocol: IETF specifications are frequently composed together. The SPAKE2 conversation defined therein may get embedded in other protocols (e.g. TLS) which have their own notion of a transcript, object encoding, or required hash functions. So the draft might not want to overspecify the protocol, for fear of inhibiting composition.

Hashing the Transcript

Finally, the transcript bytes are hashed, and the result is used as the shared key. The library must choose the hash function to use (SHA256 is a fine choice), which nails down exactly how large the shared key will be. Libraries should stick to some fixed-length hash function (either SHA256, SHA512, or BLAKE2) and return a single key. Applications which want more key material should feed this shared key into HKDF.

Hash functions can be specialized for specific purposes (the HKDF "context" argument provides this, or the BLAKE2 "personalization" string). This helps to ensure that hashes computed for one purpose won't be confused with those used for some other purpose. For SPAKE2 this doesn't seem likely, but a given library might choose to use a personalization string that captures the other implementation-specific choices that it makes. Alternatively, the transcript can include a fixed string that encapsulates the rest of the protocol (the first line could be "This is a journal about an RFC-NNNN -formatted SPAKE2 conversation", where the RFC specifies the hashes and groups and fixed elements and everything else). But of course using the name of the specification in the specification itself is a circular definition that would probably sink any chances of getting the spec published.

Both sides must use the same hash function and personalization choices.

- What python-spake2-0.7 does: key = sha256(transcript)

- What draft-irtf-crfg-spake2-03 uses: left as an exercise

Things That Don't Matter (for interoperability)

SPAKE2 implementations must also choose a random secret scalar. They'll use this to compute the message that gets sent to their peer, and then they use it again on the message they receive from their peer. It is imperative to use a fresh new scalar each time they run the protocol.

This scalar must be chosen uniformly from the full range (0 <= x <

P). The considerations and techniques described

earlier are

all important, however since this scalar is kept secret,

interoperability is not affected by how any given implementation does

it.

Things That Do Matter

A summary of the choices that both sides must agree upon to achieve interoperability (some of these are made by the library's code, and others are inputs to the library):

- the two identity strings

- how identity strings are encoded into the transcript

- the group to use

- which generator of that group to use

- how group elements are encoded (for messages and the transcript)

- the "arbitrary elements" (M/N/S)

- the password

- how the password is turned into a scalar

- how the password is encoded into the transcript

- the order of things going into the transcript

- the safe-concatenation technique of the transcript

- how to hash the transcript into the final key

And additional choices that affect security (but poor choices would not show up as interoperability failures):

- using a group where discrete log is difficult

- using "arbitrary elements" without a known discrete log

- rejecting invalid encoded elements

- safely concatenating the pieces of the transcript

Testing Interoperability

The interactive nature of the protocol makes it particularly hard to write unit tests of interoperability, especially the kind where you compare a new execution transcript against a known "good" trace copied earlier. SPAKE2 is a form of ZKP ("zero-knowledge proof"): Alice is proving that she knows the same password as Bob, without revealing any other knowledge about that password. In fact the way you prove SPAKE2 is a ZKP is to demonstrate that someone who doesn't know the password could still generate a transcript that's indistinguishable from a real one.

So we can't just take a transcript of some reference implementation (say, python-spake2) and copy it into the non-interactive unit tests of a new implementation (say, spake2.rs). Testing a non-modified SPAKE2 implementation requires something interactive: either having both implementations in the same program (e.g. your Rust unit tests have to run python code too), or using an online server to query the other implementation (your unit tests must make network calls).

The key feature of SPAKE2 that enables the ZKP proof is the private scalar (selected randomly during the first function, used to construct the first message, stored in the state vector, and used again to process the second message). For the algorithm to be secure, this scalar must be selected uniformly at random from the full range of the group order, it must never be revealed outside the library, and every single run of the protocol must generate a fresh value.

So, to test two implementations against each other non-interactively, we would have to break both implementations, by forcing them to use a known scalar, rather than a unique random value. We run the reference implementation as Alice with some fixed scalar, and then copy the generated message into our unit tests. We run it again as Bob, with a different fixed scalar, and copy that message too. We combine Alice and Bob, and record the shared key.

Now, in our new implementation, we find a way to force it to use the same scalar that we used in Bob. We assert that:

- the new implementation's Bob produces the same outbound message, given the same secret scalar

- when given Alice's message, the new code produces the same shared key

This requires modifying the code. We can't exercise the random-scalar part without interaction, but we can exercise everything beyond that point. So to enable non-interactive unit tests, implementations should be factored into two parts: an outer function (called by application code) which generates a random scalar, and an inner function which accepts the scalar as input and generates the first message (and the state that's passed to the second half). The inner function should never be exposed to applications: it should be private to the library's own unit tests.

As an added benefit, the inner function is fully deterministic and purely-functional.

Testing Server

Testing SPAKE2 implementations would benefit from an online server that can perform protocol queries (with fully random values), which will emit both the normal protocol message and the normally-secret key. To help with debugging mismatches, this test server should also reveal its internal state: the secret scalar, and the full transcript. If your implementation gets a different key, you can go back and compare the intermediate values until you find the first one that doesn't match.

I'm working on one, and I know JP has something in the works too.

Conclusions

SPAKE2 is a neat protocol: it's pretty simple (as these things go), and it enables a good chunk of functionality that none of the other crypto primitives can provide.

There seems to be a long "lead time" as cryptographic protocols slowly make their way from the academic world down into the hands of everyday programmers. There's all sorts of exciting stuff waiting for you in the literature, but most of the tools that your average developer (or security engineer) will feel comfortable using are decades old. In rough order of familiarity:

| family | year introduced | age | modern example |

|---|---|---|---|

| hashes | ~1979 | ~40 years | SHA256 (2001) |

| symmetric encryption | ~50 BC (Caesar) | ~2000 years | AES (1998) |

| MACs | ~1984 (MAA/ISO8731-2) | ~30 years | HMAC (1996) |

| public-key signatures | 1977 (RSA) | ~40 years | Ed25519 (2011) |

| public-key encryption | 1977 (RSA) | ~40 years | NaCl SecretBox (2010) |

And I think the PAKE family is ready to be the next thing through this pipeline: the family as a whole was introduced with EKE in 1992 (25 years ago!), and SPAKE2 itself is now 12 years old.

But to get there, SPAKE2 must go through the same process as the rest of these protocols. We need a good specification, as well as a certain amount of evangelism, clear use cases, examples, prior art, visible trailblazers, and developer confidence. Hopefully this list of compatibility criteria can help us get there.